Can Architects Help Reform The Criminal Justice System?

An EcoChi Vital Abstract

This article was posted on July 11, 2019 by Paul Clemence, ArchDaily.

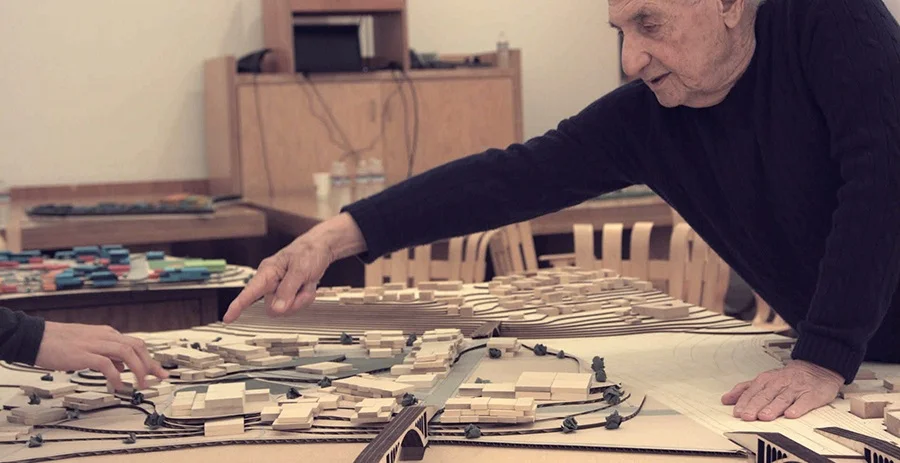

Set to screen at the ADFF:NOLA festival, Frank Gehry: Building Justice showcases how Gehry-led student architecture studios developed proposals for more humane prisons. Thanks to initiatives like the Art for Justice Fund, Open Society Foundations, and a slew of insightful reporting, the American criminal justice system has been under great scrutiny and pressure to reform. Some of these changes have been quite prominent—such as the increasingly-widespread decriminalization of pot and pending major federal legislation. However, despite the depth and breadth of criminal justice reform, one critically important element has remained mostly overlooked: the design of correctional facilities. Enter Frank Gehry, who has been focused on the subject since 2016, when he was invited by billionaire philanthropist George Soros and his Open Society Foundation to be part of a study on prison design. Gehry’s efforts, specifically student studios on prison design led by the American Canadian architect, are the focus of the documentary Frank Gehry: Building Justice, which is set to screen at the Architecture & Design Film Festival’s upcoming New Orleans edition. “What if we start treating people like human beings—what would prison look like?” asks Gehry in the documentary. Soros and the foundation’s then-director Chris Stone thought Gehry could bring outside-the-box thinking to the project, as well as higher visibility to the issue. As for Gehry, he selected the architecture studio—specifically, master-level studios at SCI-Arc and the Yale School of Architecture—as a means of introducing prison design to school curricula and planting the seeds of reform in a new generation of designers. To help further broadcast the project, Gehry asked renowned filmmaker Ultan Guilfoyle to document the process. Given the complexity of criminal justice reform, Guilfoyle worked carefully to have a low-impact presence while filming Gehry and the students throughout the process, which included studio discussions, field visits to several prisons (both domestic and abroad), and conversations with former inmates. Among the latter, Susan Burton’s story provided particularly acute insight into life behind bars: After being an inmate in California prisons for two decades, Burton managed to turn her life around and started the A New Way of Life Re-Entry Project, which helps newly freed inmates adjust to life outside. “I have had firsthand experience what it feels like to be in there, what it does to a person’s spirit and psyche,” she says in the film. “And that needed to be a part of what was thought about in this project.” A reformed system needs a more balanced view of prisons: “There are some folks that, yes, we do need to be safe from, but while we are providing that safety for our communities, how are we treating these people?” Burton accompanied the students on their trip to see Scandinavian prisons, which she says provide a far better correctional model. “The architecture there creates a place of healing, not a place of lack, of [deprivation],” she tells Metropolis. That idea of healing perhaps becomes the film’s main question: Is incarceration punishment or rehabilitation?

Copyright © 2019 EcoChi, LLC. All rights reserved.